Why Clawdbot Went Viral — And How to Build Production-Ready Long-Running Agents with LangGraph and Milvus

Clawdbot (now OpenClaw) went viral

Clawdbot, now renamed to OpenClaw, took the internet by storm last week. The open-source AI assistant built by Peter Steinberger hit 110,000+ GitHub stars in just a few days. Users posted videos of it autonomously checking them into flights, managing emails, and controlling smart home devices. Andrej Karpathy, the founding engineer at OpenAI, praised it. David Sacks, a Tech founder and investor, tweeted about it. People called it “Jarvis, but real.”

Then came the security warnings.

Researchers found hundreds of exposed admin panels. The bot runs with root access by default. There’s no sandboxing. Prompt injection vulnerabilities could let attackers hijack the agent. A security nightmare.

Clawdbot went viral for a reason

Clawdbot went viral for a reason. It runs locally or on your own server. It connects to messaging apps people already use—WhatsApp, Slack, Telegram, iMessage. It remembers context over time instead of forgetting everything after each reply. It manages calendars, summarizes emails, and automates tasks across apps.

Users get the sense of a hands-off, always-on personal AI—not just a prompt-and-response tool. Its open-source, self-hosted model appeals to developers who want control and customization. And the ease of integrating with existing workflows makes it easy to share and recommend.

Two challenges for building long-running agents

Clawdbot’s popularity proves people want AI that acts, not just answers. But any agent that runs over long periods and completes real tasks—whether Clawdbot or something you build yourself—has to solve two technical challenges: memory and verification.

The memory problem shows up in multiple ways:

Agents exhaust their context window mid-task and leave behind half-finished work

They lose sight of the full task list and declare “done” too early

They can’t hand off context between sessions, so each new session starts from scratch

All of these stem from the same root: agents have no persistent memory. Context windows are finite, cross-session retrieval is limited, and progress isn’t tracked in a way agents can access.

The verification problem is different. Even when memory works, agents still mark tasks as completed after a quick unit test—without checking whether the feature actually works end-to-end.

Clawdbot addresses both. It stores memory locally across sessions and uses modular “skills” to automate browsers, files, and external services. The approach works. But it’s not production-ready. For enterprise use, you need structure, auditability, and security that Clawdbot doesn’t provide out of the box.

This article covers the same problems with production-ready solutions.

For memory, we use a two-agent architecture based on Anthropic’s research: an initializer agent that breaks projects into verifiable features, and a coding agent that works through them one at a time with clean handoffs. For semantic recall across sessions, we use Milvus, a vector database that lets agents search by meaning, not keywords.

For verification, we use browser automation. Instead of trusting unit tests, the agent tests features the way a real user would.

We’ll walk through the concepts, then show a working implementation using LangGraph and Milvus.

How the Two-Agent Architecture Prevents Context Exhaustion

Every LLM has a context window: a limit on how much text it can process at once. When an agent works on a complex task, this window fills up with code, error messages, conversation history, and documentation. Once the window is full, the agent either stops or begins to forget earlier context. For long-running tasks, this is inevitable.

Consider an agent given a simple prompt: “Build a clone of claude.ai.” The project requires authentication, chat interfaces, conversation history, streaming responses, and dozens of other features. A single agent will try to tackle everything at once. Midway through implementing the chat interface, the context window fills up. The session ends with half-written code, no documentation of what was attempted, and no indication of what works and what doesn’t. The next session inherits a mess. Even with context compaction, the new agent has to guess what the previous session was doing, debug code it didn’t write, and figure out where to resume. Hours are wasted before any new progress is made.

The Two-Fold Agent Solution

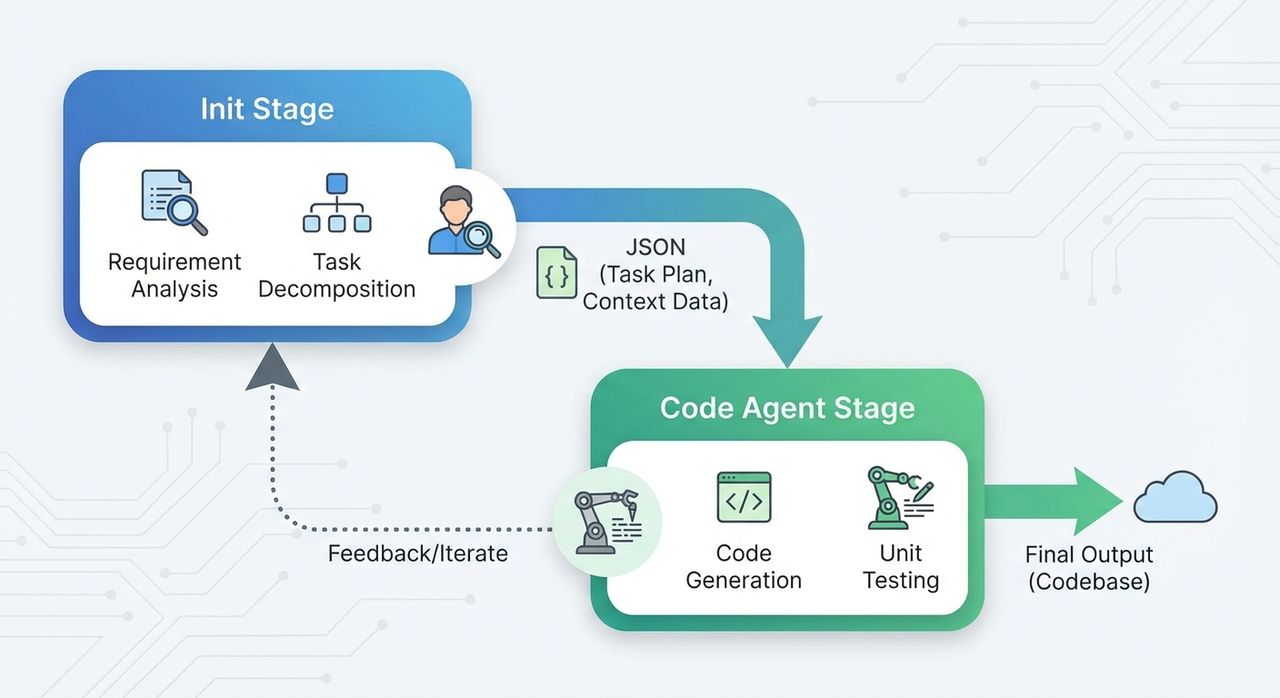

Anthropic’s solution, described in their engineering post “Effective harnesses for long-running agents”, is to use two different prompting modes: an initializer prompt for the first session and a coding prompt for subsequent sessions.

Technically, both modes use the same underlying agent, system prompt, tools, and harness. The only difference is the initial user prompt. But because they serve distinct roles, thinking of them as two separate agents is a useful mental model. We call this the two-agent architecture.

The initializer sets up the environment for incremental progress. It takes a vague request and does three things:

Breaks the project into specific, verifiable features. Not vague requirements like “make a chat interface,” but concrete, testable steps: “user clicks New Chat button → new conversation appears in sidebar → chat area shows welcome state.” Anthropic’s claude.ai clone example had over 200 such features.

Creates a progress tracking file. This file records the completion status of every feature, so any session can see what’s done and what’s left.

Writes setup scripts and makes an initial git commit. Scripts like

init.shlet future sessions spin up the dev environment quickly. The git commit establishes a clean baseline.

The initializer doesn’t just plan. It creates infrastructure that lets future sessions start working immediately.

The coding agent handles every subsequent session. It:

Reads the progress file and git logs to understand the current state

Runs a basic end-to-end test to confirm the app still works

Picks one feature to work on

Implements the feature, tests it thoroughly, commits to git with a descriptive message, and updates the progress file

When the session ends, the codebase is in a mergeable state: no major bugs, orderly code, clear documentation. There’s no half-finished work and no mystery about what was done. The next session picks up exactly where this one stopped.

Use JSON for Feature Tracking, Not Markdown

One implementation detail worth noting: the feature list should be JSON, not Markdown.

When editing JSON, AI models tend to surgically modify specific fields. When editing Markdown, they often rewrite entire sections. With a list of 200+ features, Markdown edits can accidentally corrupt your progress tracking.

A JSON entry looks like this:

json

{

"category": "functional",

"description": "New chat button creates a fresh conversation",

"steps": [

"Navigate to main interface",

"Click the 'New Chat' button",

"Verify a new conversation is created",

"Check that chat area shows welcome state",

"Verify conversation appears in sidebar"

],

"passes": false

}

Each feature has clear verification steps. The passes field tracks completion. Strongly-worded instructions like “It is unacceptable to remove or edit tests because this could lead to missing or buggy functionality” are also recommended to prevent the agent from gaming the system by deleting difficult features.

How Milvus Gives Agents Semantic Memory Across Sessions

The two-agent architecture solves context exhaustion, but it doesn’t solve forgetting. Even with clean handoffs between sessions, the agent loses track of what it learned. It can’t recall that “JWT refresh tokens” relates to “user authentication” unless those exact words appear in the progress file. As the project grows, searching through hundreds of git commits becomes slow. Keyword matching misses connections that would be obvious to a human.

This is where vector databases come in. Instead of storing text and searching for keywords, a vector database converts text into numerical representations of meaning. When you search “user authentication,” it finds entries about “JWT refresh tokens” and “login session handling.” Not because the words match, but because the concepts are semantically close. The agent can ask “have I seen something like this before?” and get a useful answer.

In practice, this works by embedding progress records and git commits into the database as vectors. When a coding session starts, the agent queries the database with its current task. The database returns relevant history in milliseconds: what was tried before, what worked, what failed. The agent doesn’t start from scratch. It starts with context.

Milvus is a good fit for this use case. It’s open source and designed for production-scale vector search, handling billions of vectors without breaking a sweat. For smaller projects or local development, Milvus Lite can be embedded directly into an application like SQLite. No cluster setup required. When the project grows, you can migrate to distributed Milvus without changing your code. For generating embeddings, you can use external models like SentenceTransformer for fine-grained control, or reference these built-in embedding functions for simpler setups. Milvus also supports hybrid search, combining vector similarity with traditional filtering, so you can query “find similar authentication issues from the last week” in a single call.

This also solves the transfer problem. The vector database persists outside of any single session, so knowledge accumulates over time. Session 50 has access to everything learned in sessions 1 through 49. The project develops institutional memory.

Verifying Completion with Automated Testing

Even with the two-agent architecture and long-term memory, agents can still declare victory too early. This is the verification problem.

Here’s a common failure mode: A coding session finishes a feature, runs a quick unit test, sees it pass, and flips "passes": false to "passes": true. But a passing unit test doesn’t mean the feature actually works. The API might return correct data while the UI displays nothing because of a CSS bug. The progress file says “complete” while users see nothing.

The solution is to make the agent test like a real user. Each feature in the feature list has concrete verification steps: “user clicks New Chat button → new conversation appears in sidebar → chat area shows welcome state.” The agent should verify these steps literally. Instead of running only code-level tests, it uses browser automation tools like Puppeteer to simulate actual usage. It opens the page, clicks buttons, fills forms, and checks that the right elements appear on screen. Only when the full flow passes does the agent mark the feature complete.

This catches problems that unit tests miss. A chat feature might have perfect backend logic and correct API responses. But if the frontend doesn’t render the reply, users see nothing. Browser automation can screenshot the result and verify that what appears on screen matches what should appear. The passes field only becomes true when the feature genuinely works end-to-end.

There are limitations, however. Some browser-native features can’t be automated by tools like Puppeteer. File pickers and system confirmation dialogs are common examples. Anthropic noted that features relying on browser-native alert modals tended to be buggier because the agent couldn’t see them through Puppeteer. The practical workaround is to design around these limitations. Use custom UI components instead of native dialogs wherever possible, so the agent can test every verification step in the feature list.

Putting It Together: LangGraph for Session State, Milvus for Long-Term Memory

The concepts above come together in a working system using two tools: LangGraph for session state and Milvus for long-term memory. LangGraph manages what’s happening within a single session: which feature is being worked on, what’s completed, what’s next. Milvus stores searchable history across sessions: what was done before, what problems were encountered, and what solutions worked. Together, they give agents both short-term and long-term memory.

A note on this implementation: The code below is a simplified demonstration. It shows the core patterns in a single script, but it doesn’t fully replicate the session separation described earlier. In a production setup, each coding session would be a separate invocation, potentially on different machines or at different times. The MemorySaver and thread_id in LangGraph enable this by persisting state between invocations. To see the resume behavior clearly, you run the script once, stop it, then run it again with the same thread_id. The second run would pick up where the first left off.

Python

from sentence_transformers import SentenceTransformer

from pymilvus import MilvusClient

from langgraph.checkpoint.memory import MemorySaver

from langgraph.graph import StateGraph, START, END

from typing import TypedDict, Annotated

import operator

import subprocess

import json

# ==================== Initialization ====================

embedding_model = SentenceTransformer('all-MiniLM-L6-v2')

milvus_client = MilvusClient("./milvus_agent_memory.db")

# Create collection

if not milvus_client.has_collection("agent_history"):

milvus_client.create_collection(

collection_name="agent_history",

dimension=384,

auto_id=True

)

# ==================== Milvus Operations ====================

def retrieve_context(query: str, top_k: int = 3):

"""Retrieve relevant history from Milvus (core element: semantic retrieval)"""

query_vec = embedding_model.encode(query).tolist()

results = milvus_client.search(

collection_name="agent_history",

data=[query_vec],

limit=top_k,

output_fields=["content"]

)

if results and results[0]:

return [hit["entity"]["content"] for hit in results[0]]

return []

def save_progress(content: str):

"""Save progress to Milvus (long-term memory)"""

embedding = embedding_model.encode(content).tolist()

milvus_client.insert(

collection_name="agent_history",

data=[{"vector": embedding, "content": content}]

)

# ==================== Core Element 1: Git Commit ====================

def git_commit(message: str):

"""Git commit (core element from the article)"""

try:

# In a real project, actual Git commands would be executed

# subprocess.run(["git", "add", "."], check=True)

# subprocess.run(["git", "commit", "-m", message], check=True)

print(f"[Git Commit] {message}")

return True

except Exception as e:

print(f"[Git Commit Failed] {e}")

return False

# ==================== Core Element 2: Test Verification ====================

def run_tests(feature: str):

"""Run tests (end-to-end testing emphasized in the article)"""

try:

# In a real project, testing tools like Puppeteer would be called

# Simplified to simulated testing here

print(f"[Test Verification] Testing feature: {feature}")

# Simulated test result

test_passed = True # In practice, this would return actual test results

if test_passed:

print(f"[Test Passed] {feature}")

return test_passed

except Exception as e:

print(f"[Test Failed] {e}")

return False

# ==================== State Definition ====================

class AgentState(TypedDict):

messages: Annotated[list, operator.add]

features: list # All features list

completed_features: list # Completed features

current_feature: str # Currently processing feature

session_count: int # Session counter

# ==================== Two-Agent Nodes ====================

def initialize_node(state: AgentState):

"""Initializer Agent: Generate feature list and set up work environment"""

print("\n========== Initializer Agent Started ==========")

# Generate feature list (in practice, a detailed feature list would be generated based on requirements)

features = [

"Implement user registration",

"Implement user login",

"Implement password reset",

"Implement user profile editing",

"Implement session management"

]

# Save initialization info to Milvus

init_summary = f"Project initialized with {len(features)} features"

save_progress(init_summary)

print(f"[Initialization Complete] Feature list: {features}")

return {

**state,

"features": features,

"completed_features": [],

"current_feature": features[0] if features else "",

"session_count": 0,

"messages": [init_summary]

}

def code_node(state: AgentState):

"""Coding Agent: Implement, test, commit (core loop node)"""

print(f"\n========== Coding Agent Session #{state['session_count'] + 1} ==========")

current_feature = state["current_feature"]

print(f"[Current Task] {current_feature}")

# ===== Core Element 3: Retrieve history from Milvus (cross-session memory) =====

print(f"[Retrieving History] Querying experiences related to '{current_feature}'...")

context = retrieve_context(current_feature)

if context:

print(f"[Retrieval Results] Found {len(context)} relevant records:")

for i, ctx in enumerate(context, 1):

print(f" {i}. {ctx[:60]}...")

else:

print("[Retrieval Results] No relevant history (first time implementing this type of feature)")

# ===== Step 1: Implement feature =====

print(f"[Starting Implementation] {current_feature}")

# In practice, an LLM would be called to generate code

implementation_result = f"Implemented feature: {current_feature}"

# ===== Step 2: Test verification (core element) =====

test_passed = run_tests(current_feature)

if not test_passed:

print(f"[Session End] Tests did not pass, fixes needed")

return state # Don't proceed if tests fail

# ===== Step 3: Git commit (core element) =====

commit_message = f"feat: {current_feature}"

git_commit(commit_message)

# ===== Step 4: Update progress file =====

print(f"[Updating Progress] Marking feature as complete")

# ===== Step 5: Save to Milvus long-term memory =====

progress_record = f"Completed feature: {current_feature} | Commit message: {commit_message} | Test status: passed"

save_progress(progress_record)

# ===== Step 6: Update state and prepare for next feature =====

new_completed = state["completed_features"] + [current_feature]

remaining_features = [f for f in state["features"] if f not in new_completed]

print(f"[Progress] Completed: {len(new_completed)}/{len(state['features'])}")

# ===== Core Element 4: Session end (clear session boundary) =====

print(f"[Session End] Codebase is in clean state, safe to interrupt\n")

return {

**state,

"completed_features": new_completed,

"current_feature": remaining_features[0] if remaining_features else "",

"session_count": state["session_count"] + 1,

"messages": [implementation_result]

}

# ==================== Core Element 3: Loop Control ====================

def should_continue(state: AgentState):

"""Determine whether to continue to next feature (incremental loop development)"""

if state["current_feature"] and state["current_feature"] != "":

return "code" # Continue to next feature

else:

print("\n========== All Features Complete ==========")

return END

# ==================== Build Workflow ====================

workflow = StateGraph(AgentState)

# Add nodes

workflow.add_node("initialize", initialize_node)

workflow.add_node("code", code_node)

# Add edges

workflow.add_edge(START, "initialize")

workflow.add_edge("initialize", "code")

# Add conditional edges (implement loop)

workflow.add_conditional_edges(

"code",

should_continue,

{

"code": "code", # Continue loop

END: END # End

}

)

# Compile workflow (using MemorySaver as checkpointer)

app = workflow.compile(checkpointer=MemorySaver())

# ==================== Usage Example: Demonstrating Cross-Session Recovery ====================

if __name__ == "__main__":

print("=" * 60)

print("Demo Scenario: Multi-Session Development for Long-Running Agents")

print("=" * 60)

# ===== Session 1: Initialize + complete first 2 features =====

print("\n[Scenario 1] First launch: Complete first 2 features")

config = {"configurable": {"thread_id": "project_001"}}

result = app.invoke({

"messages": [],

"features": [],

"completed_features": [],

"current_feature": "",

"session_count": 0

}, config)

print("\n" + "=" * 60)

print("[Simulated Scenario] Developer manually interrupts (Ctrl+C) or context window exhausted")

print("=" * 60)

# ===== Session 2: Restore state from checkpoint =====

print("\n[Scenario 2] New session starts: Continue from last interruption")

print("Using the same thread_id, LangGraph automatically restores from checkpoint...")

# Using the same thread_id, LangGraph will automatically restore state from checkpoint

result = app.invoke({

"messages": [],

"features": [],

"completed_features": [],

"current_feature": "",

"session_count": 0

}, config)

print("\n" + "=" * 60)

print("Demo Complete!")

print("=" * 60)

print("\nKey Takeaways:")

print("1. ✅ Two-Agent Architecture (initialize + code)")

print("2. ✅ Incremental Loop Development (conditional edges control loop)")

print("3. ✅ Git Commits (commit after each feature)")

print("4. ✅ Test Verification (end-to-end testing)")

print("5. ✅ Session Management (clear session boundaries)")

print("6. ✅ Cross-Session Recovery (thread_id + checkpoint)")

print("7. ✅ Semantic Retrieval (Milvus long-term memory)")

**The key insight is in the last part.** By using the same `thread_id`, LangGraph automatically restores the checkpoint from the previous session. Session 2 picks up exactly where session 1 stopped — no manual state transfer, no lost progress.

Conclusion

AI agents fail at long-running tasks because they lack persistent memory and proper verification. Clawdbot went viral by solving these problems, but its approach isn’t production-ready.

This article covered three solutions that are:

Two-agent architecture: An initializer breaks projects into verifiable features; a coding agent works through them one at a time with clean handoffs. This prevents context exhaustion and makes progress trackable.

Vector database for semantic memory: Milvus stores progress records and git commits as embeddings, so agents can search by meaning, not keywords. Session 50 remembers what session 1 learned.

Browser automation for real verification: Unit tests verify that the code runs. Puppeteer checks if features actually work by testing what users see on screen.

These patterns aren’t limited to software development. Scientific research, financial modeling, legal document review—any task that spans multiple sessions and requires reliable handoffs can benefit.

The core principles:

Use an initializer to break work into verifiable chunks

Track progress in a structured, machine-readable format

Store experience in a vector database for semantic retrieval

Verify completion with real-world testing, not just unit tests

Design for clean session boundaries so work can pause and resume safely

The tools exist. The patterns are proven. What remains is applying them.

Ready to get started?

Explore Milvus and Milvus Lite for adding semantic memory to your agents

Check out LangGraph for managing session state

Read Anthropic’s full research on long-running agent harnesses

Have questions or want to share what you’re building?

Join the Milvus Slack community to connect with other developers

Attend Milvus Office Hours for live Q&A with the team

- Clawdbot (now OpenClaw) went viral

- Clawdbot went viral for a reason

- Two challenges for building long-running agents

- How the Two-Agent Architecture Prevents Context Exhaustion

- The Two-Fold Agent Solution

- Use JSON for Feature Tracking, Not Markdown

- How Milvus Gives Agents Semantic Memory Across Sessions

- Verifying Completion with Automated Testing

- Putting It Together: LangGraph for Session State, Milvus for Long-Term Memory

- Conclusion

On This Page

Try Managed Milvus for Free

Zilliz Cloud is hassle-free, powered by Milvus and 10x faster.

Get StartedLike the article? Spread the word