Reflections on ChatGPT and Claude’s Memory Systems: What It Takes to Enable On-Demand Conversational Retrieval

In high-quality AI agent systems, memory design is far more complex than it first appears. At its core, it must answer three fundamental questions: How should conversation history be stored? When should past context be retrieved? And what, exactly, should be retrieved?

These choices directly shape an agent’s response latency, resource usage, and—ultimately—its capability ceiling.

Models like ChatGPT and Claude feel increasingly “memory-aware” the more we use them. They remember preferences, adapt to long-term goals, and maintain continuity across sessions. In that sense, they already function as mini AI agents. Yet beneath the surface, their memory systems are built on very different architectural assumptions.

Recent reverse-engineering analyses of ChatGPT’s and Claude’s memory mechanisms reveal a clear contrast. ChatGPT relies on precomputed context injection and layered caching to deliver lightweight, predictable continuity. Claude, by contrast, adopts RAG-style, on-demand retrieval with dynamic memory updates to balance memory depth and efficiency.

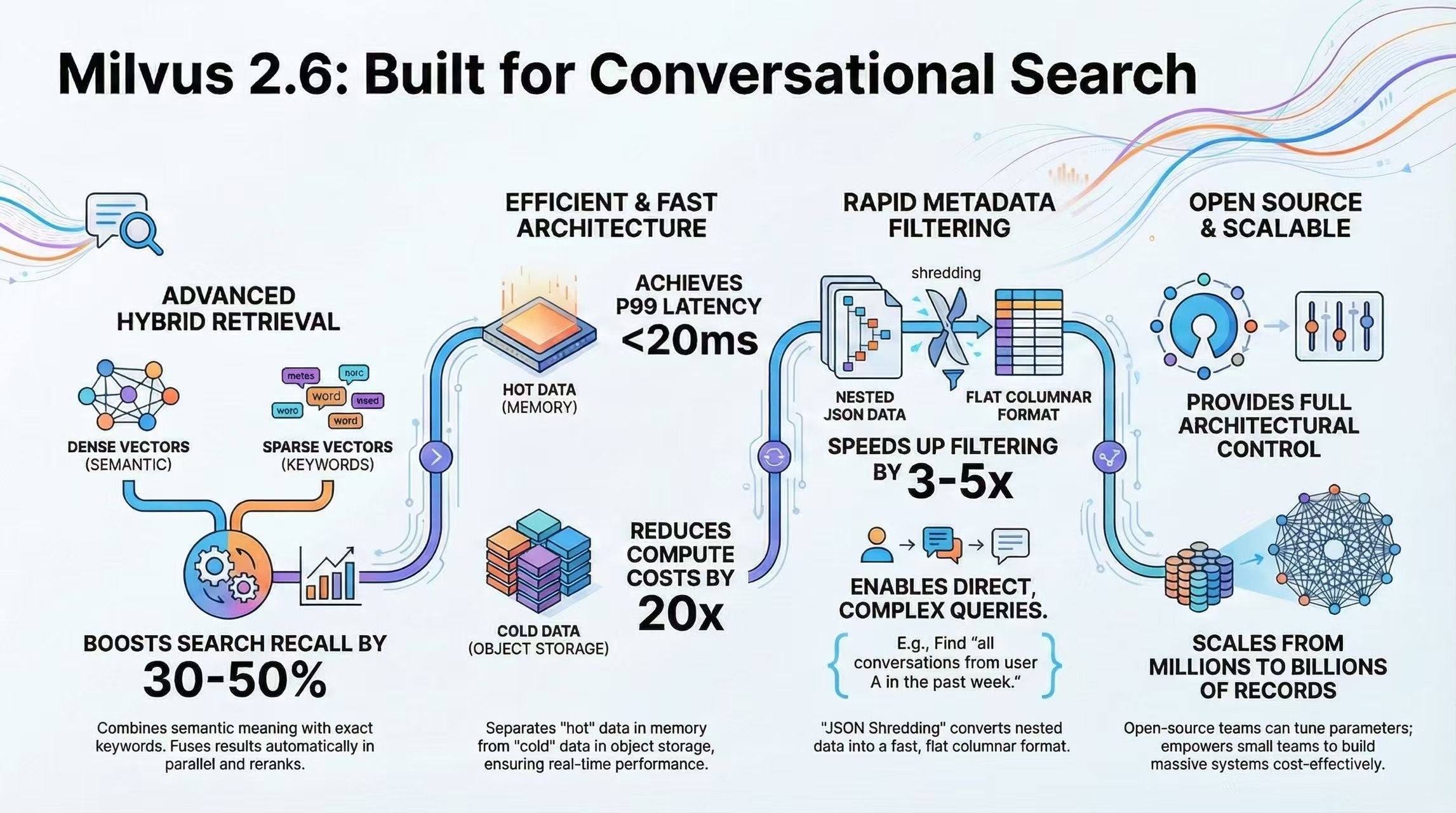

These two approaches are not just design preferences—they are shaped by infrastructure capability. Milvus 2.6 introduces the combination of hybrid dense–sparse retrieval, efficient scalar filtering, and tiered storage that on-demand conversational memory requires, making selective retrieval fast and economical enough to deploy in real-world systems.

In this post, we’ll walk through how ChatGPT’s and Claude’s memory systems actually work, why they diverged architecturally, and how recent advances in systems like Milvus make on-demand conversational retrieval practical at scale.

ChatGPT’s Memory System

Instead of querying a vector database or dynamically retrieving past conversations at inference time, ChatGPT constructs its “memory” by assembling a fixed set of context components and injecting them directly into every prompt. Each component is prepared ahead of time and occupies a known position in the prompt.

This design keeps personalization and conversational continuity intact while making latency, token usage, and system behavior more predictable. In other words, memory is not something the model searches for on the fly—it is something the system packages and hands to the model every time it generates a response.

At a high level, a complete ChatGPT prompt consists of the following layers, ordered from most global to most immediate:

[0] System Instructions

[1] Developer Instructions

[2] Session Metadata (ephemeral)

[3] User Memory (long-term facts)

[4] Recent Conversations Summary (past chats, titles + snippets)

[5] Current Session Messages (this chat)

[6] Your latest message

Among these, components [2] through [5] form the effective memory of the system, each serving a distinct role.

Session Metadata

Session metadata represents short-lived, non-persistent information that is injected once at the beginning of a conversation and discarded when the session ends. Its role is to help the model adapt to the current usage context rather than to personalize behavior long term.

This layer captures signals about the user’s immediate environment and recent usage patterns. Typical signals include:

Device information — for example, whether the user is on mobile or desktop

Account attributes — such as subscription tier (for example, ChatGPT Go), account age, and overall usage frequency

Behavioral metrics — including active days over the past 1, 7, and 30 days, average conversation length, and model usage distribution (for example, 49% of requests handled by GPT-5)

User Memory

User memory is the persistent, editable layer of memory that enables personalization across conversations. It stores relatively stable information—such as a user’s name, role or career goals, ongoing projects, past outcomes, and learning preferences—and is injected into each new conversation to preserve continuity over time.

This memory can be updated in two ways:

Explicit updates occur when users directly manage memory with instructions like “remember this” or “remove this from memory.”

Implicit updates occur when the system identifies information that meets OpenAI’s storage criteria—such as a confirmed name or job title—and saves it automatically, subject to the user’s default consent and memory settings.

Recent Conversation Summary

The recent conversation summary is a lightweight, cross-session context layer that preserves continuity without replaying or retrieving full chat histories. Instead of relying on dynamic retrieval, as in traditional RAG-based approaches, this summary is precomputed and injected directly into every new conversation.

This layer summarizes user messages only, excluding assistant replies. It is intentionally limited in size—typically around 15 entries—and retains only high-level signals about recent interests rather than detailed content. Because it does not rely on embeddings or similarity search, it keeps both latency and token consumption low.

Current Session Messages

Current session messages contain the full message history of the ongoing conversation and provide the short-term context needed for coherent, turn-by-turn responses. This layer includes both user inputs and assistant replies, but only while the session remains active.

Because the model operates within a fixed token limit, this history cannot grow indefinitely. When the limit is reached, the system drops the earliest messages to make room for newer ones. This truncation affects only the current session: long-term user memory and the recent conversation summary remain intact.

Claude’s Memory System

Claude takes a different approach to memory management. Rather than injecting a large, fixed bundle of memory components into every prompt—as ChatGPT does—Claude combines persistent user memory with on-demand tools and selective retrieval. Historical context is fetched only when the model judges it to be relevant, allowing the system to trade off contextual depth against computational cost.

Claude’s prompt context is structured as follows:

[0] System Prompt (static instructions)

[1] User Memories

[2] Conversation History

[3] Current Message

The key differences between Claude and ChatGPT lie in how conversation history is retrieved and how user memory is updated and maintained.

User Memories

In Claude, user memories form a long-term context layer similar in purpose to ChatGPT’s user memory, but with a stronger emphasis on automatic, background-driven updates. These memories are stored in a structured format (wrapped in XML-style tags) and are designed to evolve gradually over time with minimal user intervention.

Claude supports two update paths:

Implicit updates — The system periodically analyzes conversation content and updates memory in the background. These updates are not applied in real time, and memories associated with deleted conversations are gradually pruned as part of ongoing optimization.

Explicit updates — Users can directly manage memory through commands such as “remember this” or “delete this,” which are executed via a dedicated

memory_user_editstool.

Compared with ChatGPT, Claude places greater responsibility on the system itself to refine, update, and prune long-term memory. This reduces the need for users to actively curate what is stored.

Conversation History

For conversation history, Claude does not rely on a fixed summary that is injected into every prompt. Instead, it retrieves past context only when the model decides it is necessary, using three distinct mechanisms. This avoids carrying irrelevant history forward and keeps token usage under control.

| Component | Purpose | How It’s Used |

|---|---|---|

| Rolling Window (Current Conversation) | Stores the full message history of the current conversation (not a summary), similar to ChatGPT’s session context | Injected automatically. Token limit is ~190K; older messages are dropped once the limit is reached |

conversation_search tool | Searches past conversations by topic or keyword, returning conversation links, titles, and user/assistant message excerpts | Triggered when the model determines that historical details are needed. Parameters include query (search terms) and max_results (1–10) |

recent_chats tool | Retrieves recent conversations within a specified time range (for example, “past 3 days”), with results formatted the same as conversation_search | Triggered when the recent, time-scoped context is relevant. Parameters include n (number of results), sort_order, and time range |

Among these components, conversation_search is especially noteworthy. It can surface relevant results even for loosely phrased or multilingual queries, indicating that it operates at a semantic level rather than relying on simple keyword matching. This likely involves embedding-based retrieval, or a hybrid approach that first translates or normalizes the query into a canonical form and then applies keyword or hybrid retrieval.

Overall, Claude’s on-demand retrieval approach has several notable strengths:

Retrieval is not automatic: Tool calls are triggered by the model’s own judgment. For example, when a user refers to “the project we discussed last time,” Claude may decide to invoke

conversation_searchto retrieve the relevant context.Richer context when needed: Retrieved results can include assistant response excerpts, whereas ChatGPT’s summaries only capture user messages. This makes Claude better suited for use cases that require deeper or more precise conversational context.

Better efficiency by default: Because historical context is not injected unless needed, the system avoids carrying large amounts of irrelevant history forward, reducing unnecessary token consumption.

The trade-offs are equally clear. Introducing on-demand retrieval increases system complexity: indexes must be built and maintained, queries executed, results ranked, and sometimes re-ranked. End-to-end latency also becomes less predictable than with precomputed, always-injected context. In addition, the model must learn to decide when retrieval is necessary. If that judgment fails, relevant context may never be fetched at all.

The Constraints Behind Claude-Style On-Demand Retrieval

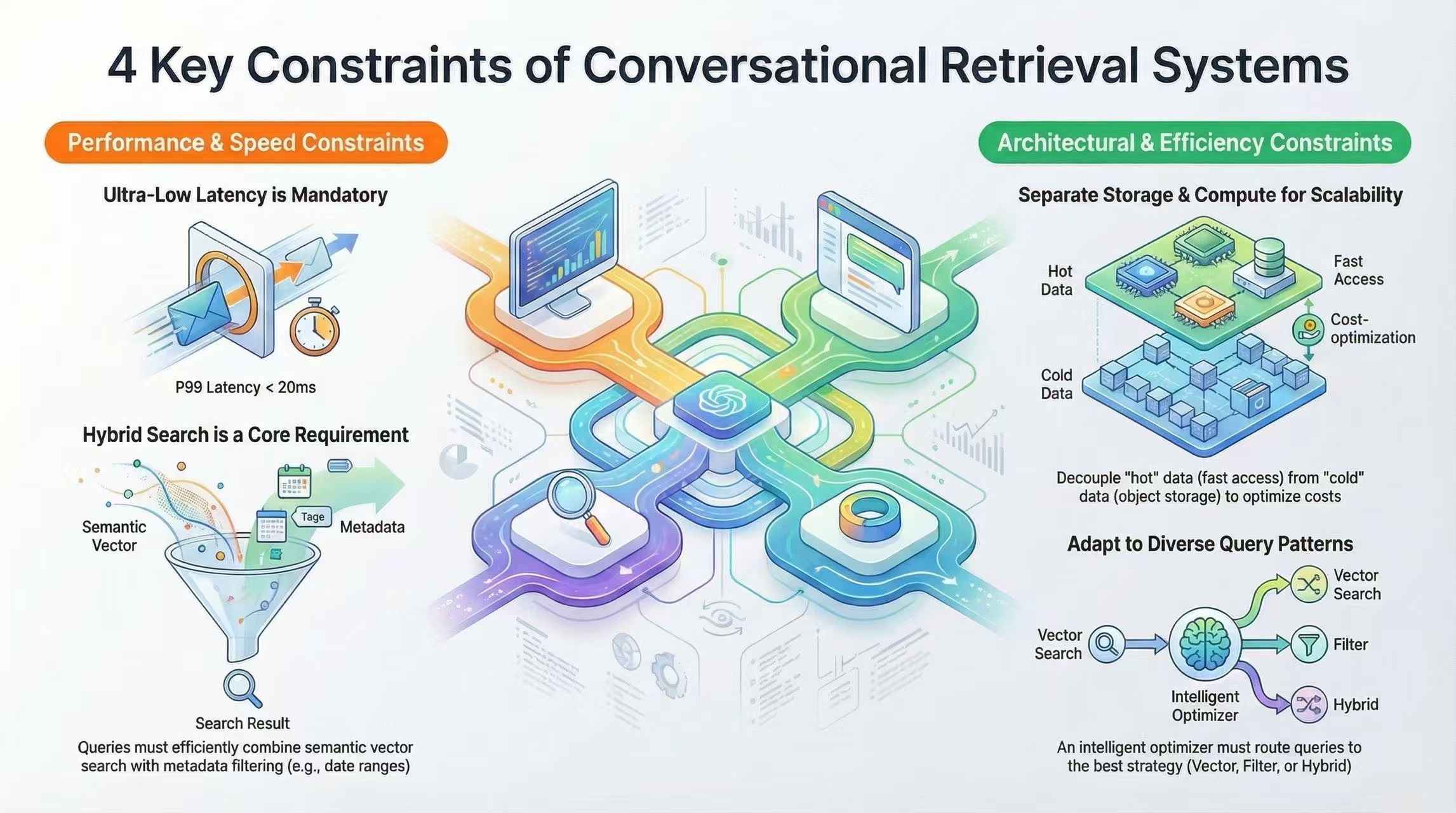

Adopting an on-demand retrieval model makes the vector database a critical part of the architecture. Conversation retrieval places unusually high demands on both storage and query execution, and the system must meet four constraints at the same time.

1. Low Latency Tolerance

In conversational systems, P99 latency typically needs to stay under ~20 ms. Delays beyond that are immediately noticeable to users. This leaves little room for inefficiency: vector search, metadata filtering, and result ranking must all be carefully optimized. A bottleneck at any point can degrade the entire conversational experience.

2. Hybrid Search Requirement

User queries often span multiple dimensions. A request like “discussions about RAG from the past week” combines semantic relevance with time-based filtering. If a database only supports vector search, it may return 1,000 semantically similar results, only for application-layer filtering to reduce them to a handful—wasting most of the computation. To be practical, the database must natively support combined vector and scalar queries.

3. Storage–Compute Separation

Conversation history exhibits a clear hot–cold access pattern. Recent conversations are queried frequently, while older ones are rarely touched. If all vectors had to stay in memory, storing tens of millions of conversations would consume hundreds of gigabytes of RAM—an impractical cost at scale. To be viable, the system must support storage–compute separation, keeping hot data in memory and cold data in object storage, with vectors loaded on demand.

4. Diverse Query Patterns

Conversation retrieval does not follow a single access pattern. Some queries are purely semantic (for example, “the performance optimization we discussed”), others are purely temporal (“all conversations from last week”), and many combine multiple constraints (“Python-related discussions mentioning FastAPI in the last three months”). The database query planner must adapt execution strategies to different query types, rather than relying on a one-size-fits-all, brute-force search.

Together, these four challenges define the core constraints of conversational retrieval. Any system seeking to implement Claude-style, on-demand retrieval must address all of them in a coordinated way.

Why Milvus 2.6 Works Well for Conversational Retrieval

The design choices in Milvus 2.6 align closely with the core requirements of on-demand conversational retrieval. Below is a breakdown of the key capabilities and how they map to real conversational retrieval needs.

Hybrid Retrieval with Dense and Sparse Vectors

Milvus 2.6 natively supports storing dense and sparse vectors within the same collection and automatically fusing their results at query time. Dense vectors (for example, 768-dimensional embeddings generated by models like BGE-M3) capture semantic similarity, while sparse vectors (typically produced by BM25) preserve exact keyword signals.

For a query such as “discussions about RAG from last week,” Milvus executes semantic retrieval and keyword retrieval in parallel, then merges the results through reranking. Compared to using either approach alone, this hybrid strategy delivers significantly higher recall in real conversational scenarios.

Storage–Compute Separation and Query Optimization

Milvus 2.6 supports tiered storage in two ways:

Hot data in memory, cold data in object storage

Indexes in memory, raw vector data in object storage

With this design, storing one million conversation entries can be achieved with roughly 2 GB of memory and 8 GB of object storage. With proper tuning, P99 latency can remain below 20 ms, even with storage–compute separation enabled.

JSON Shredding and Fast Scalar Filtering

Milvus 2.6 enables JSON Shredding by default, flattening nested JSON fields into columnar storage. This improves scalar filtering performance by 3–5× according to official benchmarks (actual gains vary by query pattern).

Conversational retrieval often requires filtering by metadata such as user ID, session ID, or time range. With JSON Shredding, queries like “all conversations from user A in the past week” can be executed directly on columnar indexes, without repeatedly parsing full JSON blobs.

Open-Source Control and Operational Flexibility

As an open-source system, Milvus offers a level of architectural and operational control that closed, black-box solutions do not. Teams can tune index parameters, apply data tiering strategies, and customize distributed deployments to match their workloads.

This flexibility lowers the barrier to entry: small and mid-sized teams can build million- to tens-of-millions-scale conversational retrieval systems without relying on oversized infrastructure budgets.

Why ChatGPT and Claude Took Different Paths

At a high level, the difference between ChatGPT’s and Claude’s memory systems comes down to how each handles forgetting. ChatGPT favors proactive forgetting: once memory exceeds fixed limits, older context is dropped. This trades completeness for simplicity and predictable system behavior. Claude favors delayed forgetting. In theory, conversation history can grow without bound, with recall delegated to an on-demand retrieval system.

So why did the two systems choose different paths? With the technical constraints laid out above, the answer becomes clear: each architecture is only viable if the underlying infrastructure can support it.

If Claude’s approach had been attempted in 2020, it would likely have been impractical. At the time, vector databases often incurred hundreds of milliseconds of latency, hybrid queries were poorly supported, and resource usage scaled prohibitively as data grew. Under those conditions, on-demand retrieval would have been dismissed as over-engineering.

By 2025, the landscape has changed. Advances in infrastructure—driven by systems such as Milvus 2.6—have made storage–compute separation, query optimization, dense–sparse hybrid retrieval, and JSON Shredding viable in production. These advances reduce latency, control costs, and make selective retrieval practical at scale. As a result, on-demand tools and retrieval-based memory have become not only feasible, but increasingly attractive, especially as a foundation for agent-style systems.

Ultimately, architecture choices follow what the infrastructure makes possible.

Conclusion

In real-world systems, memory design is not a binary choice between precomputed context and on-demand retrieval. The most effective architectures are typically hybrid, combining both approaches.

A common pattern is to inject recent conversation turns through a sliding context window, store stable user preferences as fixed memory, and retrieve older history on demand via vector search. As a product matures, this balance can shift gradually—from primarily precomputed context to increasingly retrieval-driven—without requiring a disruptive architectural reset.

Even when starting with a precomputed approach, it is important to design with migration in mind. Memory should be stored with clear identifiers, timestamps, categories, and source references. When retrieval becomes viable, embeddings can be generated for existing memory and added to a vector database alongside the same metadata, allowing retrieval logic to be introduced incrementally and with minimal disruption.

Have questions or want a deep dive on any feature of the latest Milvus? Join our Discord channel or file issues on GitHub. You can also book a 20-minute one-on-one session to get insights, guidance, and answers to your questions through Milvus Office Hours.

- ChatGPT’s Memory System

- Session Metadata

- User Memory

- Recent Conversation Summary

- Current Session Messages

- Claude’s Memory System

- User Memories

- Conversation History

- The Constraints Behind Claude-Style On-Demand Retrieval

- 1. Low Latency Tolerance

- 2. Hybrid Search Requirement

- 3. Storage–Compute Separation

- 4. Diverse Query Patterns

- Why Milvus 2.6 Works Well for Conversational Retrieval

- Hybrid Retrieval with Dense and Sparse Vectors

- Storage–Compute Separation and Query Optimization

- JSON Shredding and Fast Scalar Filtering

- Open-Source Control and Operational Flexibility

- Why ChatGPT and Claude Took Different Paths

- Conclusion

On This Page

Try Managed Milvus for Free

Zilliz Cloud is hassle-free, powered by Milvus and 10x faster.

Get StartedLike the article? Spread the word