Is RAG Becoming Outdated Now That Long-Running Agents Like Claude Cowork Are Emerging?

Claude Cowork is a new agent feature in the Claude Desktop app. From a developer’s point of view, it’s basically an automated task runner wrapped around the model: it can read, modify, and generate local files, and it can plan multi-step tasks without you having to manually prompt for each step. Think of it as the same loop behind Claude Code, but exposed to the desktop instead of the terminal.

Cowork’s key capability is its ability to run for extended periods without losing state. It doesn’t hit the usual conversation timeout or context reset. It can keep working, track intermediate results, and reuse previous information across sessions. That gives the impression of “long-term memory,” even though the underlying mechanics are more like persistent task state + contextual carryover. Either way, the experience is different from the traditional chat model, where everything resets unless you build your own memory layer.

This brings up two practical questions for developers:

If the model can already remember past information, where does RAG or agentic RAG still fit in? Will RAG be replaced?

If we want a local, Cowork-style agent, how do we implement long-term memory ourselves?

The rest of this article addresses these questions in detail and explains how vector databases fit into this new “model memory” landscape.

Claude Cowork vs. RAG: What’s the Difference?

As I mentioned previously, Claude Cowork is an agent mode inside Claude Desktop that can read and write local files, break tasks into smaller steps, and keep working without losing state. It maintains its own working context, so multi-hour tasks don’t reset like a normal chat session.

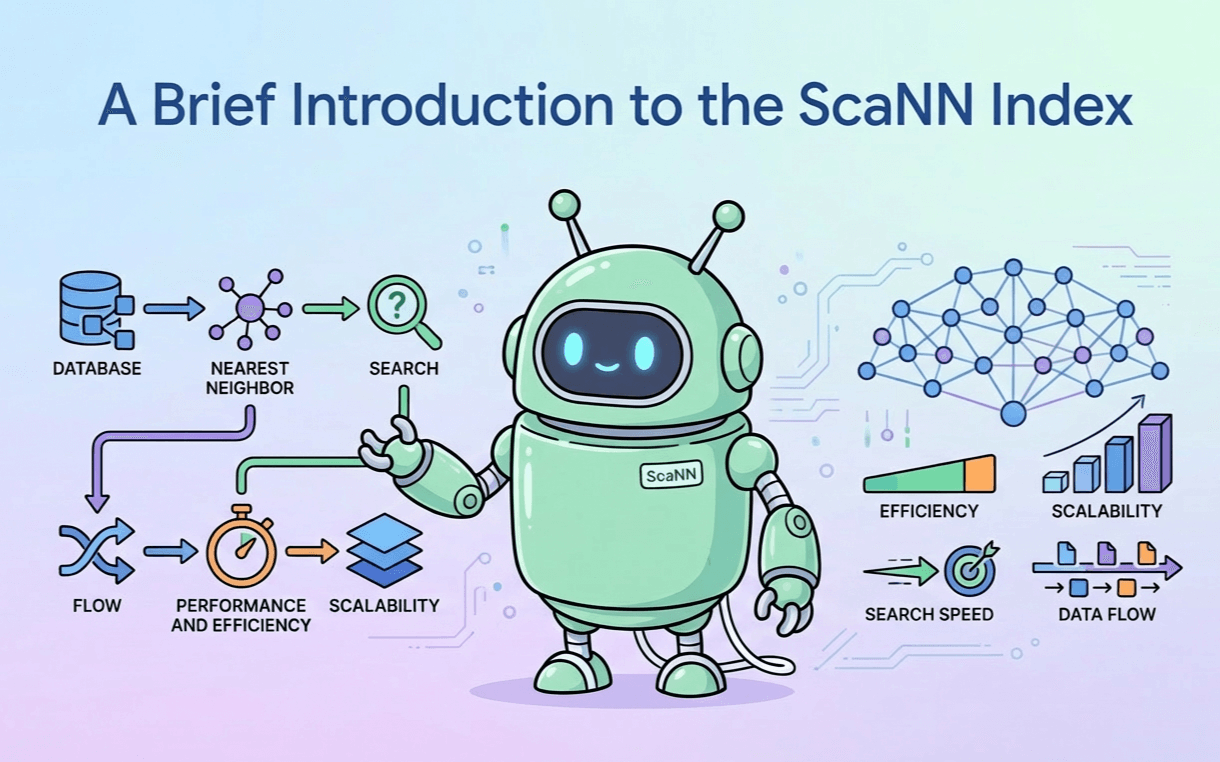

RAG (Retrieval-Augmented Generation) solves a different problem: giving a model access to external knowledge. You index your data into a vector database, retrieve relevant chunks for each query, and feed them into the model. It’s widely used because it provides LLM applications with a form of “long-term memory” for documents, logs, product data, and more.

If both systems help a model “remember,” what’s the actual difference?

How Cowork Handles Memory

Cowork’s memory is read-write. The agent decides which information from the current task or conversation is relevant, stores it as memory entries, and retrieves it later as the task progresses. This allows Cowork to maintain continuity across long-running workflows — especially ones that produce new intermediate state as they progress.

How RAG and Agentic RAG Handle Memory

Standard RAG is query-driven retrieval: the user asks something, the system fetches relevant documents, and the model uses them to answer. The retrieval corpus stays stable and versioned, and developers control exactly what enters it.

Modern agentic RAG extends this pattern. The model can decide when to retrieve information, what to retrieve, and how to use it during the planning or execution of a workflow. These systems can run long tasks and call tools, similar to Cowork. But even with agentic RAG, the retrieval layer remains knowledge-oriented rather than state-oriented. The agent retrieves authoritative facts; it doesn’t write its evolving task state back into the corpus.

Another way to look at it:

Cowork’s memory is task-driven: the agent writes and reads its own evolving state.

RAG is knowledge-driven: the system retrieves established information that the model should rely on.

Reverse-Engineering Claude Cowork: How It Builds Long-Running Agent Memory

Cowork gets a lot of hype because it handles multi-step tasks without constantly forgetting what it was doing. From a developer’s perspective, I am wondering how it keeps state across such long sessions? Anthropic hasn’t published the internals, but based on earlier dev experiments with Claude’s memory module, we can piece together a decent mental model.

Claude seems to rely on a hybrid setup: a persistent long-term memory layer plus on-demand retrieval tools. Instead of stuffing the full conversation into every request, Claude selectively pulls in past context only when it decides it’s relevant. This lets the model keep accuracy high without blowing through tokens every turn.

If you break down the request structure, it roughly looks like this:

[0] Static system instructions

[1] User memory (long-term)

[2] Retrieved / pruned conversation history

[3] Current user message

The interesting behavior isn’t the structure itself — it’s how the model decides what to update and when to run retrieval.

User Memory: The Persistent Layer

Claude keeps a long-term memory store that updates over time. And unlike ChatGPT’s more predictable memory system, Claude’s feels a bit more “alive.” It stores memories in XML-ish blocks and updates them in two ways:

Implicit updates: Sometimes the model just decides something is a stable preference or fact and quietly writes it to memory. These updates aren’t instantaneous; they show up after a few turns, and older memories can fade out if the related conversation disappears.

Explicit updates: Users can directly modify memory with the

memory_user_editstool (“remember X,” “forget Y”). These writes are immediate and behave more like a CRUD operation.

Claude is running background heuristics to decide what’s worth persisting, and it’s not waiting for explicit instructions.

Conversation Retrieval: The On-Demand Part

Claude does not keep a rolling summary like many LLM systems. Instead, it has a toolbox of retrieval functions it can call whenever it thinks it’s missing context. These retrieval calls don’t happen every turn — the model triggers them based on its own internal judgment.

The standout is conversation_search. When the user says something vague like “that project from last month,” Claude often fires this tool to dig up relevant turns. What’s notable is that it still works when the phrasing is ambiguous or in a different language. That pretty clearly implies:

Some kind of semantic matching (embeddings)

Probably combined with normalization or lightweight translation

Keyword search layered in for precision

Basically, this looks a lot like a miniature RAG system bundled inside the model’s toolset.

How Claude’s Retrieval Behavior Differs From Basic History Buffers

From testing and logs, a few patterns stand out:

Retrieval isn’t automatic. The model chooses when to call it. If it thinks it already has enough context, it won’t even bother.

Retrieved chunks include both user and assistant messages. That’s useful — it keeps more nuance than user-only summaries.

Token usage stays sane. Because history isn’t injected every turn, long sessions don’t balloon unpredictably.

Overall, it feels like a retrieval-augmented LLM, except the retrieval happens as part of the model’s own reasoning loop.

This architecture is clever, but not free:

Retrieval adds latency and more “moving parts” (indexing, ranking, re-ranking).

The model occasionally misjudges whether it needs context, which means you see the classic “LLM forgetfulness” even though the data was available.

Debugging becomes trickier because model behavior depends on invisible tool triggers, not just prompt input.

Claude Cowork vs Claude Codex in handling long-term memory

In contrast to Claude’s retrieval-heavy setup, ChatGPT handles memory in a much more structured and predictable way. Instead of doing semantic lookups or treating old conversations like a mini vector store, ChatGPT injects memory directly into each session through the following layered components:

User memory

Session metadata

Current session messages

User Memory

User Memory is the main long-term storage layer—the part that persists across sessions and can be edited by the user. It stores pretty standard things: name, background, ongoing projects, learning preferences, that kind of stuff. Every new conversation gets this block injected at the start, so the model always starts with a consistent view of the user.

ChatGPT updates this layer in two ways:

Explicit updates: Users can tell the model to “remember this” or “forget that,” and the memory changes immediately. This is basically a CRUD API that the model exposes through natural language.

Implicit updates: If the model spots information that fits OpenAI’s rules for long-term memory—like a job title or a preference—and the user hasn’t disabled memory, it will quietly add it on its own.

From a developer angle, this layer is simple, deterministic, and easy to reason about. No embedding lookups, no heuristics about what to fetch.

Session Metadata

Session Metadata sits at the opposite end of the spectrum. It’s short-lived, non-persistent, and only injected once at the start of a session. Think of it as environment variables for the conversation. This includes things like:

what device you’re on

account/subscription state

rough usage patterns (active days, model distribution, average conversation length)

This metadata helps the model shape responses for the current environment—e.g., writing shorter answers on mobile—without polluting long-term memory.

Current Session Messages

This is the standard sliding-window history: all messages in the current conversation until the token limit is reached. When the window gets too large, older turns drop off automatically.

Crucially, this eviction does not touch User Memory or cross-session summaries. Only the local conversation history shrinks.

The biggest divergence from Claude appears in how ChatGPT handles “recent but not current” conversations. Claude will call a search tool to retrieve past context if it thinks it’s relevant. ChatGPT does not do that.

Instead, ChatGPT keeps a very lightweight cross-session summary that gets injected into every conversation. A few key details about this layer:

It summarizes only user messages, not assistant messages.

It stores a very small set of items—roughly 15—just enough to capture stable themes or interests.

It does no embedding computation, no similarity ranking, and no retrieval calls. It’s basically pre-chewed context, not dynamic lookup.

From an engineering perspective, this approach trades flexibility for predictability. There’s no chance of a weird retrieval failure, and inference latency stays stable because nothing is being fetched on the fly. The downside is that ChatGPT won’t pull in some random message from six months ago unless it made it into the summary layer.

Challenges to Making Agent Memory Writable

When an agent moves from read-only memory (typical RAG) to writable memory—where it can log user actions, decisions, and preferences—the complexity jumps quickly. You’re no longer just retrieving documents; you’re maintaining a growing state on which the model depends.

A writable memory system has to solve three real problems:

What to remember: The agent needs rules for deciding which events, preferences, or observations are worth keeping. Without this, memory either explodes in size or fills with noise.

How to store and tier memory: Not all memory is equal. Recent items, long-term facts, and ephemeral notes all need different storage layers, retention policies, and indexing strategies.

How to write fast without breaking retrieval: Memory must be written continuously, but frequent updates can degrade index quality or slow queries if the system isn’t designed for high-throughput inserts.

Challenge 1: What Is Worth Remembering?

Not everything a user does should end up in long-term memory. If someone creates a temp file and deletes it five minutes later, recording that forever doesn’t help anyone. This is the core difficulty: how does the system decide what actually matters?

(1) Common ways to judge importance

Teams usually rely on a mix of heuristics:

Time-based: recent actions matter more than old ones

Frequency-based: files or actions accessed repeatedly are more important

Type-based: some objects are inherently more important (for example, project config files vs. cache files)

(2) When rules conflict

These signals often conflict. A file created last week but edited heavily today—should age or activity win? There’s no single “correct” answer, which is why importance scoring tends to get messy fast.

(3) How vector databases help

Vector databases give you mechanisms to enforce importance rules without manual cleanup:

TTL: Milvus can automatically remove data after a set time

Decay: older vectors can be down-weighted so they naturally fade from retrieval

Challenge 2: Memory Tiering in Practice

As agents run longer, memory piles up. Keeping everything in fast storage isn’t sustainable, so the system needs a way to split memory into hot (frequently accessed) and cold (rarely accessed) tiers.

(1) Deciding When Memory Becomes Cold

In this model, hot memory refers to data kept in RAM for low-latency access, while cold memory refers to data moved to disk or object storage to reduce cost.

Deciding when memory becomes cold can be handled in different ways. Some systems use lightweight models to estimate the semantic importance of an action or file based on its meaning and recent usage. Others rely on simple, rule-based logic, such as moving memory that has not been accessed for 30 days or has not appeared in retrieval results for a week. Users may also explicitly mark certain files or actions as important, ensuring they always remain hot.

(2) Where Hot and Cold Memory Are Stored

Once classified, hot and cold memories are stored differently. Hot memory stays in RAM and is used for frequently accessed content, such as active task context or recent user actions. Cold memory is moved to disk or object storage systems like S3, where access is slower but storage costs are much lower. This trade-off works well because cold memory is rarely needed and is typically accessed only for long-term reference.

(3) How Vector Databases Help

Milvus and Zilliz Cloud support this pattern by enabling hot–cold tiered storage while maintaining a single query interface, so frequently accessed vectors stay in memory and older data moves to lower-cost storage automatically.

Challenge 3: How Fast Should Memory Be Written?

Traditional RAG systems usually write data in batches. Indexes are rebuilt offline—often overnight—and only become searchable later. This approach works for static knowledge bases, but it does not fit agent memory.

(1) Why Agent Memory Needs Real-Time Writes

Agent memory must capture user actions as they happen. If an action is not recorded immediately, the next conversation turn may lack critical context. For this reason, writable memory systems require real-time writes rather than delayed, offline updates.

(2) The Tension Between Write Speed and Retrieval Quality

Real-time memory demands very low write latency. At the same time, high-quality retrieval depends on well-built indexes, and index construction takes time. Rebuilding an index for every write is too expensive, but delaying indexing means newly written data remains temporarily invisible to retrieval. This trade-off sits at the center of writable memory design.

(3) How Vector Databases Help

Vector databases address this problem by decoupling writing from indexing. A common solution is to stream writes and perform incremental index builds. Using Milvus as an example, new data is first written to an in-memory buffer, allowing the system to handle high-frequency writes efficiently. Even before a full index is built, buffered data can be queried within seconds through dynamic merging or approximate search.

When the buffer reaches a predefined threshold, the system builds indexes in batches and persists them. This improves long-term retrieval performance without blocking real-time writes. By separating fast ingestion from slower index construction, Milvus achieves a practical balance between write speed and search quality that works well for agent memory.

Conclusion

Cowork gives us a glimpse of a new class of agents—persistent, stateful, and able to carry context across long timelines. But it also makes something else clear: long-term memory is only half of the picture. To build production-ready agents that are both autonomous and reliable, we still need structured retrieval over large, evolving knowledge bases.

RAG handles the world’s facts; writable memory handles the agent’s internal state. And vector databases sit at the intersection, providing indexing, hybrid search, and scalable storage that enable both layers to work together.

As long-running agents continue to mature, their architectures will likely converge on this hybrid design. Cowork is a strong signal of where things are heading—not toward a world without RAG, but toward agents with richer memory stacks powered by vector databases underneath.

If you want to explore these ideas or get help with your own setup, join our Slack Channel to chat with Milvus engineers. And for more hands-on guidance, you can always book a Milvus Office Hours session.

- Claude Cowork vs. RAG: What’s the Difference?

- How Cowork Handles Memory

- How RAG and Agentic RAG Handle Memory

- Reverse-Engineering Claude Cowork: How It Builds Long-Running Agent Memory

- User Memory: The Persistent Layer

- Conversation Retrieval: The On-Demand Part

- How Claude’s Retrieval Behavior Differs From Basic History Buffers

- Claude Cowork vs Claude Codex in handling long-term memory

- Challenges to Making Agent Memory Writable

- Challenge 1: What Is Worth Remembering?

- Challenge 2: Memory Tiering in Practice

- Challenge 3: How Fast Should Memory Be Written?

- Conclusion

On This Page

Try Managed Milvus for Free

Zilliz Cloud is hassle-free, powered by Milvus and 10x faster.

Get StartedLike the article? Spread the word