Embedding First, Then Chunking: Smarter RAG Retrieval with Max–Min Semantic Chunking

Retrieval Augmented Generation (RAG) has become the default approach for providing context and memory for AI applications — AI agents, customer support assistants, knowledge bases, and search systems all rely on it.

In almost every RAG pipeline, the standard process is the same: take the documents, split them into chunks, and then embed those chunks for similarity retrieval in a vector database like Milvus. Because chunking happens upfront, the quality of those chunks directly affects how well the system retrieves information and how accurate the final answers are.

The issue is that traditional chunking strategies usually split text without any semantic understanding. Fixed-length chunking cuts based on token counts, and recursive chunking uses surface-level structure, but both still ignore the actual meaning of the text. As a result, related ideas often get separated, unrelated lines get grouped together, and important context gets fragmented.

In this blog, I’d like to share a different chunking strategy: Max–Min Semantic Chunking. Instead of chunking first, it embeds the text upfront and uses semantic similarity to decide where boundaries should form. By embedding before cutting, the pipeline can track natural shifts in meaning rather than relying on arbitrary length limits.

How a Typical RAG Pipeline Works

Most RAG pipelines, regardless of the framework, follow the same four-stage assembly line. You’ve probably written some version of this yourself:

1. Data Cleaning and Chunking

The pipeline starts by cleaning the raw documents: removing headers, footers, navigation text, and anything that isn’t real content. Once the noise is out, the text gets split into smaller pieces. Most teams use fixed-size chunks — typically 300–800 tokens — because it keeps the embedding model manageable. The downside is that the splits are based on length, not meaning, so the boundaries can be arbitrary.

2. Embedding and Storage

Each chunk is then embedded using an embedding model like OpenAI’s text-embedding-3-small or BAAI’s encoder. The resulting vectors are stored in a vector database such as Milvus or Zilliz Cloud. The database handles indexing and similarity search so you can quickly compare new queries against all stored chunks.

3. Querying

When a user asks a question — for example, “How does RAG reduce hallucinations?” — the system embeds the query and sends it to the database. The database returns the top-K chunks whose vectors are closest to the query. These are the pieces of text the model will rely on to answer the question.

4. Answer Generation

The retrieved chunks are bundled together with the user query and fed into an LLM. The model generates an answer using the provided context as grounding.

Chunking sits at the start of this whole pipeline, but it has an outsized impact. If the chunks align with the natural meaning of the text, retrieval feels accurate and consistent. If the chunks were cut in awkward places, the system has a harder time finding the right information, even with strong embeddings and a fast vector database.

The Challenges of Getting Chunking Right

Most RAG systems today use one of two basic chunking methods, both of which have limitations.

1. Fixed-size chunking

This is the simplest approach: split the text by a fixed token or character count. It’s fast and predictable, but completely unaware of grammar, topics, or transitions. Sentences can get cut in half. Sometimes even words. The embeddings you get from these chunks tend to be noisy because the boundaries don’t reflect how the text is actually structured.

2. Recursive character splitting

This method is a bit smarter. It splits text hierarchically based on cues like paragraphs, line breaks, or sentences. If a section is too long, it recursively divides it further. The output is generally more coherent, but still inconsistent. Some documents lack clear structure or have uneven section lengths, which hurts retrieval accuracy. And in some cases, this approach still produces chunks that exceed the model’s context window.

Both methods face the same tradeoff: precision vs. context. Smaller chunks improve retrieval accuracy but lose surrounding context; larger chunks preserve meaning but risk adding irrelevant noise. Striking the right balance is what makes chunking both foundational—and frustrating—in RAG system design.

Max–Min Semantic Chunking: Embed First, Chunk Later

In 2025, S.R. Bhat et al. published Rethinking Chunk Size for Long-Document Retrieval: A Multi-Dataset Analysis. One of their key findings was that there isn’t a single “best” chunk size for RAG. Small chunks (64–128 tokens) tend to work better for factual or lookup-style questions, while larger chunks (512–1024 tokens) help with narrative or high-level reasoning tasks. In other words, fixed-size chunking is always a compromise.

This raises a natural question: instead of picking one length and hoping for the best, can we chunk by meaning rather than size? Max–Min Semantic Chunking is one approach I found that tries to do precisely that.

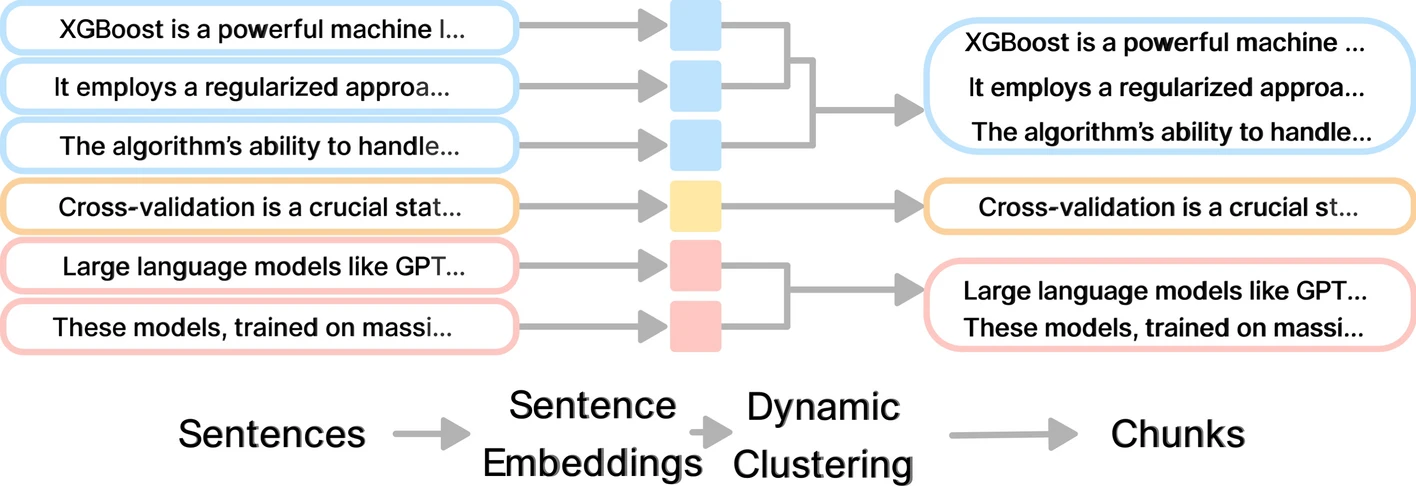

The idea is simple: embed first, chunk second. Instead of splitting text and then embedding whatever pieces fall out, the algorithm embeds all sentences up front. It then uses the semantic relationships between those sentence embeddings to decide where the boundaries should go.

Diagram showing embed-first chunk-second workflow in Max-Min Semantic Chunking

Diagram showing embed-first chunk-second workflow in Max-Min Semantic Chunking

Conceptually, the method treats chunking as a constrained clustering problem in embedding space. You walk through the document in order, one sentence at a time. For each sentence, the algorithm compares its embedding with those in the current chunk. If the new sentence is semantically close enough, it joins the chunk. If it’s too far, the algorithm starts a new chunk. The key constraint is that chunks must follow the original sentence order — no reordering, no global clustering.

The result is a set of variable-length chunks that reflect where the document’s meaning actually changes, instead of where a character counter happens to hit zero.

How the Max–Min Semantic Chunking Strategy Works

Max–Min Semantic Chunking determines chunk boundaries by comparing how sentences relate to one another in the high-dimensional vector space. Instead of relying on fixed lengths, it looks at how meaning shifts across the document. The process can be broken down into six steps:

1. Embed all sentences and start a chunk

The embedding model converts each sentence in the document into a vector embedding. It processes sentences in order. If the first n–k sentences form the current chunk C, the following sentence (sₙ₋ₖ₊₁) needs to be evaluated: should it join C, or start a new chunk?

2. Measure how consistent the current chunk is

Within chunk C, calculate the minimum pairwise cosine similarity among all sentence embeddings. This value reflects how closely related the sentences within the chunk are. A lower minimum similarity indicates that the sentences are less related, suggesting that the chunk may need to be split.

3. Compare the new sentence to the chunk

Next, calculate the maximum cosine similarity between the new sentence and any sentence already in C. This reflects how well the new sentence aligns semantically with the existing chunk.

4. Decide whether to extend the chunk or start a new one

This is the core rule:

If the new sentence’s max similarity to chunk C is greater than or equal to the minimum similarity inside C, → The new sentence fits and stays in the chunk.

Otherwise, → start a new chunk.

This ensures that each chunk maintains its internal semantic consistency.

5. Adjust thresholds as the document changes

To optimize chunk quality, parameters such as chunk size and similarity thresholds can be adjusted dynamically. This allows the algorithm to adapt to varying document structures and semantic densities.

6. Handle the first few sentences

When a chunk contains only one sentence, the algorithm handles the first comparison using a fixed similarity threshold. If the similarity between sentence 1 and sentence 2 is above that threshold, they form a chunk. If not, they split immediately.

Strengths and Limitations of Max–Min Semantic Chunking

Max–Min Semantic Chunking improves how RAG systems split text by using meaning instead of length, but it’s not a silver bullet. Here’s a practical look at what it does well and where it still falls short.

What It Does Well

Max–Min Semantic Chunking improves on traditional chunking in three important ways:

1. Dynamic, meaning-driven chunk boundaries

Unlike fixed-size or structure-based approaches, this method relies on semantic similarity to guide chunking. It compares the minimum similarity within the current chunk (how cohesive it is) to the maximum similarity between the new sentence and that chunk (how well it fits). If the latter is higher, the sentence joins the chunk; otherwise, a new chunk starts.

2. Simple, practical parameter tuning

The algorithm depends on just three core hyperparameters:

the maximum chunk size,

the minimum similarity between the first two sentences, and

the similarity threshold for adding new sentences.

These parameters adjust automatically with context—larger chunks require stricter similarity thresholds to maintain coherence.

3. Low processing overhead

Because the RAG pipeline already computes sentence embeddings, Max–Min Semantic Chunking doesn’t add heavy computation. All it needs is a set of cosine similarity checks while scanning through sentences. This makes it cheaper than many semantic chunking techniques that require extra models or multi-stage clustering.

What It Still Can’t Solve

Max–Min Semantic Chunking improves chunk boundaries, but it doesn’t eliminate all the challenges of document segmentation. Because the algorithm processes sentences in order and only clusters locally, it can still miss long-range relationships in longer or more complex documents.

One common issue is context fragmentation. When important information is spread across different parts of a document, the algorithm may place those pieces into separate chunks. Each chunk then carries only part of the meaning.

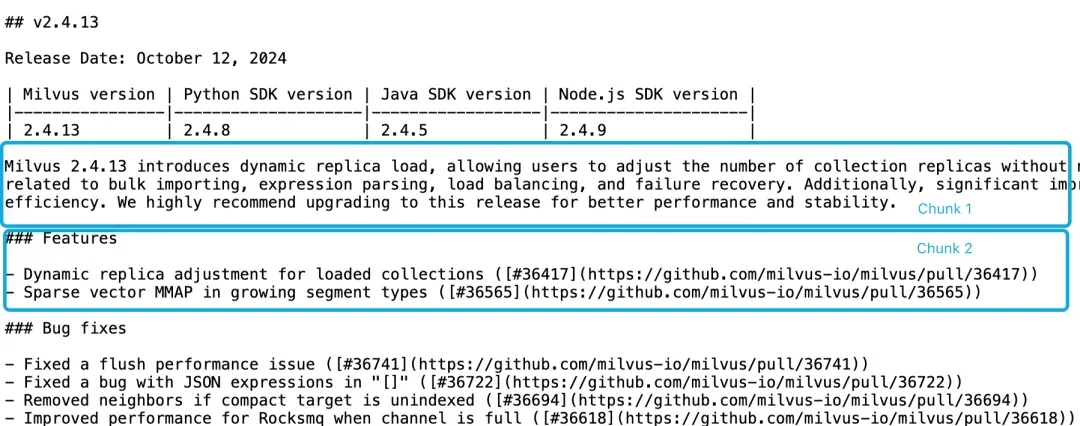

For example, in the Milvus 2.4.13 Release Notes, as shown below, one chunk might contain the version identifier while another contains the feature list. A query like “What new features were introduced in Milvus 2.4.13?” depends on both. If those details are split across different chunks, the embedding model may not connect them, leading to weaker retrieval.

-

Example showing context fragmentation in Milvus 2.4.13 Release Notes with version identifier and feature list in separate chunks

Example showing context fragmentation in Milvus 2.4.13 Release Notes with version identifier and feature list in separate chunks

This fragmentation also affects the LLM generation stage. If the version reference is in one chunk and the feature descriptions are in another, the model receives incomplete context and can’t reason cleanly about the relationship between the two.

To mitigate these cases, systems often use techniques such as sliding windows, overlapping chunk boundaries, or multi-pass scans. These approaches reintroduce some of the missing context, reduce fragmentation, and help the retrieval step retain related information.

Conclusion

Max–Min Semantic Chunking isn’t a magic fix for every RAG problem, but it does give us a more sane way to think about chunk boundaries. Instead of letting token limits decide where ideas get chopped, it uses embeddings to detect where the meaning actually shifts. For many real-world documents—APIs, specs, logs, release notes, troubleshooting guides—this alone can push retrieval quality noticeably higher.

What I like about this approach is that it fits naturally into existing RAG pipelines. If you already embed sentences or paragraphs, the extra cost is basically a few cosine similarity checks. You don’t need extra models, complex clustering, or heavyweight preprocessing. And when it works, the chunks it produces feel more “human”—closer to how we mentally group information when reading.

But the method still has blind spots. It only sees meaning locally, and it can’t reconnect information that’s intentionally spread apart. Overlapping windows, multi-pass scans, and other context-preserving tricks are still necessary, especially for documents where references and explanations live far from each other.

Still, Max–Min Semantic Chunking moves us in the right direction: away from arbitrary text slicing and toward retrieval pipelines that actually respect semantics. If you’re exploring ways to make RAG more reliable, it’s worth experimenting with.

Have questions or want to dig deeper into improving RAG performance? Join our Discord and connect with engineers who are building and tuning real retrieval systems every day.

- How a Typical RAG Pipeline Works

- 1. Data Cleaning and Chunking

- 2. Embedding and Storage

- 3. Querying

- 4. Answer Generation

- The Challenges of Getting Chunking Right

- Max–Min Semantic Chunking: Embed First, Chunk Later

- How the Max–Min Semantic Chunking Strategy Works

- 1. Embed all sentences and start a chunk

- 2. Measure how consistent the current chunk is

- 3. Compare the new sentence to the chunk

- 4. Decide whether to extend the chunk or start a new one

- 5. Adjust thresholds as the document changes

- 6. Handle the first few sentences

- Strengths and Limitations of Max–Min Semantic Chunking

- What It Does Well

- What It Still Can’t Solve

- Conclusion

On This Page

Try Managed Milvus for Free

Zilliz Cloud is hassle-free, powered by Milvus and 10x faster.

Get StartedLike the article? Spread the word